Burgos Cathedral: El Cid's Tomb, The Golden Staircase, and The "Papamoscas"

- AMCL Schatz

- Jan 15, 2023

- 7 min read

After a hearty breakfast of traditional Galician fare at the hotel’s famed restaurant, we drove to Burgos, the historic capital for five centuries of the unified Old Castile-León region in Spain.

Burgos is situated on the Pilgrim’s Road to Santiago de Compostela and boasts an array of Spanish Gothic architectural masterpieces, most notably the Catedral de Santa Maria de Burgos, declared a World Heritage site by UNESCO, and is also the burial place of the legendary hero, El Cid.

We arrived in the mid-afternoon and checked in a simple hotel a stone’s throw away from the cathedral. Our accommodation was a far cry from the previous night’s, and the complete opposite of everything modern. The building was a lot older, the rooms a lot smaller, and the interior was screaming out for renovation, from the old-fashioned elevator to the yellowish claw-foot tub and black-and-white checkered tiles in the bathroom. The décor, from the floral curtains to the circa 1960s dresser, could also use some updating. Surprisingly though, it felt very homey and the hotel staff were super friendly. The best thing about this hotel is the location, for it was a mere five-minute walk to the cathedral.

As soon as I deposited my luggage in my room, I ventured out with my amigas. It was a glorious sunny day and according to our Tour Director, there was much going on at the cathedral plaza.

We knew we were getting closer when we saw the Arco de Santa Maria, the imposing entrance to the Old Town. From a distance, it looked like a castle. It was built in the 14th century as a triumphal arch in honor of Emperor Carlos V, and was renovated in 1552. The massive arch is flanked by two semi-circular towers and features statues of Castilian kings and noblemen. We were told that the interior is often used to display temporary art exhibitions.

After walking through the arch, we reached Plaza del Rey San Fernando and got our first glimpse of the Catedral de Santa Maria de Burgos. It was a busy square indeed. Aside from the usual tourist crowd, a group of locals were in the middle of preparation for some event. There were folks in costumes, musicians, and even police cars.

But the frenzy around did not overshadow the majestic presence of the cathedral, built of marble-like limestone and decorated in the most extravagant style.

We walked to its western façade called the Puerta Principal facing the Plaza del Santa Maria to view the towers from upfront. Crowned by magnificent octagonal spires with open stonework traceries and enhanced by balustrades and balconies with detailed carvings and pinnacles, they are quite remarkable. Standing proud on either side, it was like they were raising up the town’s prayers to the heavens.

The façade, where the regular churchgoers (i.e., the ones attending religious services) enter, has three storeys and triple entrances framed by three-dimensional arches. The central door is known as the Puerta del Perdon doorway with a gallery of statues of Castile monarchs. The side doors are dedicated to Our Lady of the Assumption and the Immaculate Conception. Above the doorway is a beautiful star-patterned Cistercian rose window.

But as the tourist (i.e., visitors who are just sightseeing) entrance is located on the southern side known as the Puerta del Sarmental, we walked back to Plaza del Rey San Fernando. This entrance is considerably lower than its opposite on the north side but still higher than street level, so we had to climb a flight of stairs. The door features the image of Christ seated, giving a blessing with His right hand and holding a book on His left, surrounded by the apostles and the evangelists, as well as a choir of angels. The reliefs are very detailed and realistic indeed. No wonder, it is said to be the doorway where the most beautiful group of sculptures can be found.

Given that the foundation was laid in 1221 and construction finally completed in 1567, the church is a silent testament of history and a comprehensive example of the evolution of Gothic style. It is also a veritable exhibit of Gothic art. If one views it from different sides, the structure’s shape and character seem to constantly change. And this is just the exterior. I couldn’t wait to see what magnificent sights I would see inside. We were told that the cathedral holds a superb collection of art – paintings, sculptures, altar pieces, tombs, stained-glass windows, furniture, and ceremonial objects.

Our local guide led us through the tourists’ entrance, where we skipped the queue and were immediately given maps and headsets for our personal audio tour. The cathedral is one of the few European churches that still hold Masses and religious rites. I had visited others that have been turned into full-fledged museums and no longer function as a worship place. But at the time of our visit, there was no service.

The church has a cruciform floor plan with a long nave, wide aisles, and a total of nineteen chapels surrounding it. I did not know where to start, but I suddenly remembered my headset. I followed the itinerary suggested by the audio guide.

The first stop was the high altar dominated by a huge 16th century piece in the Gothic-Flamenco style. The huge retablo is carved in walnut, heavily-gilded in gold, and features statues of saints in five tiers. Above us, the dome of the main nave is topped by beautiful Mudejar (Moorish-style) vault. In the centre of the vault is the stunning cimborrio (lantern). Below it are two-storied slender stained-glass windows, gilded balustrades, superb reliefs, sculptures and coats of arms. The light coming from the sky through the eight-sided star window gave the chapel an ethereal glow.

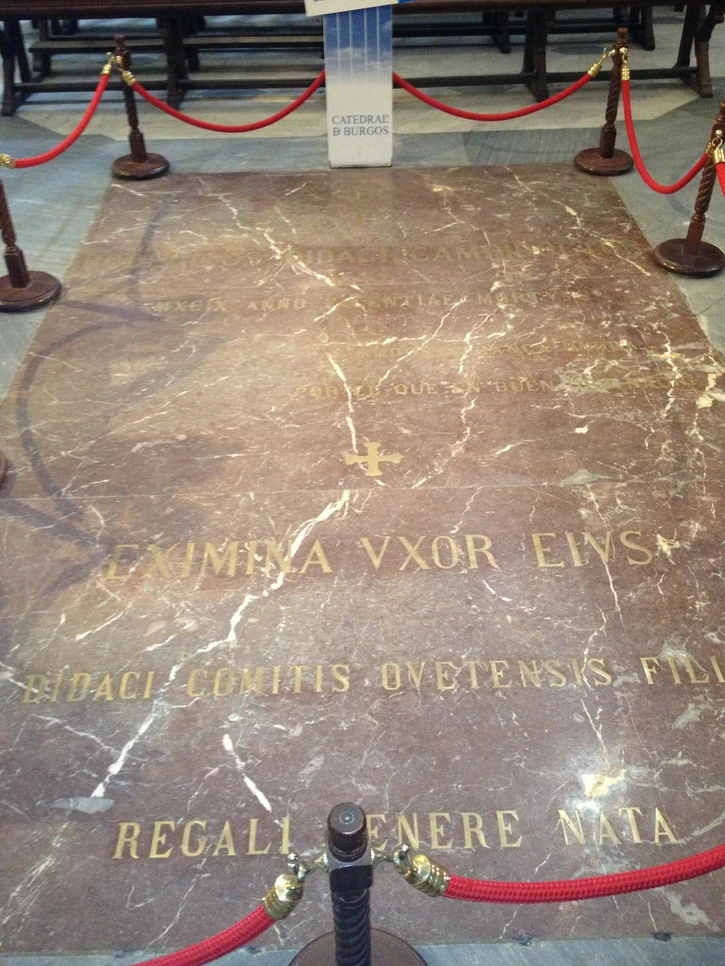

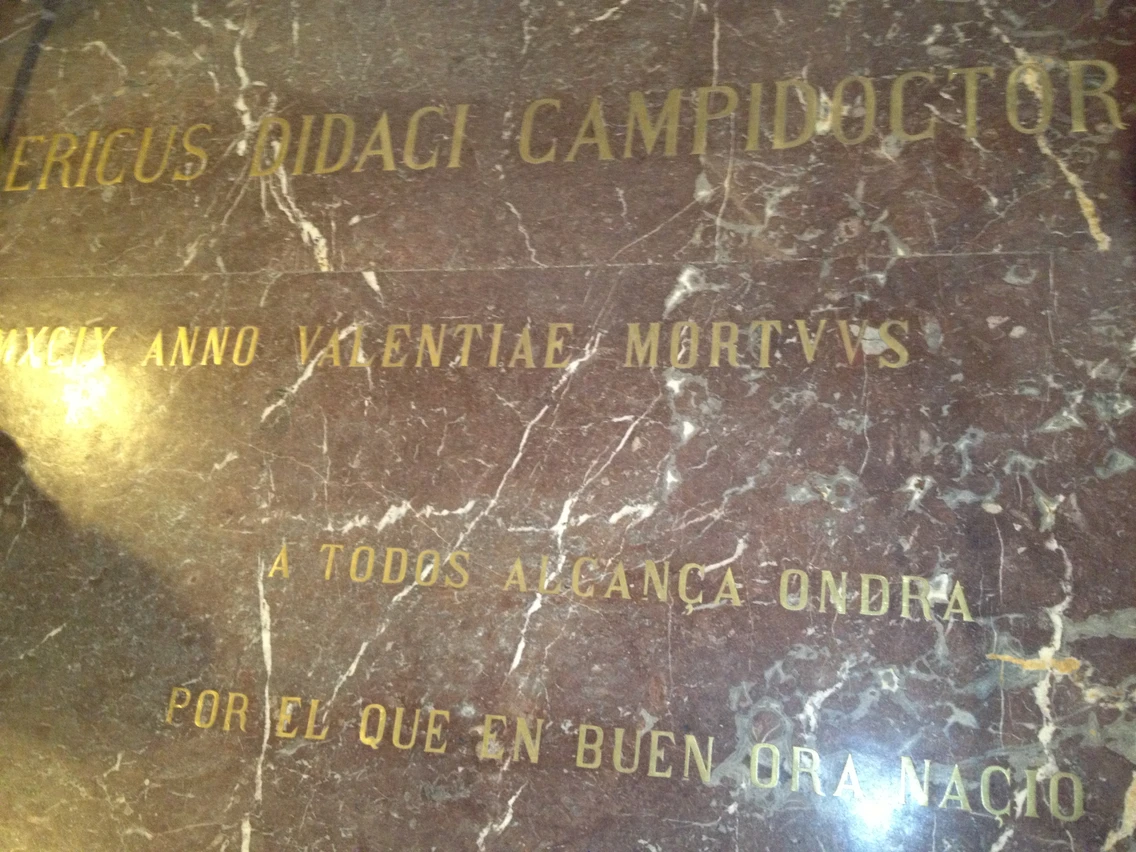

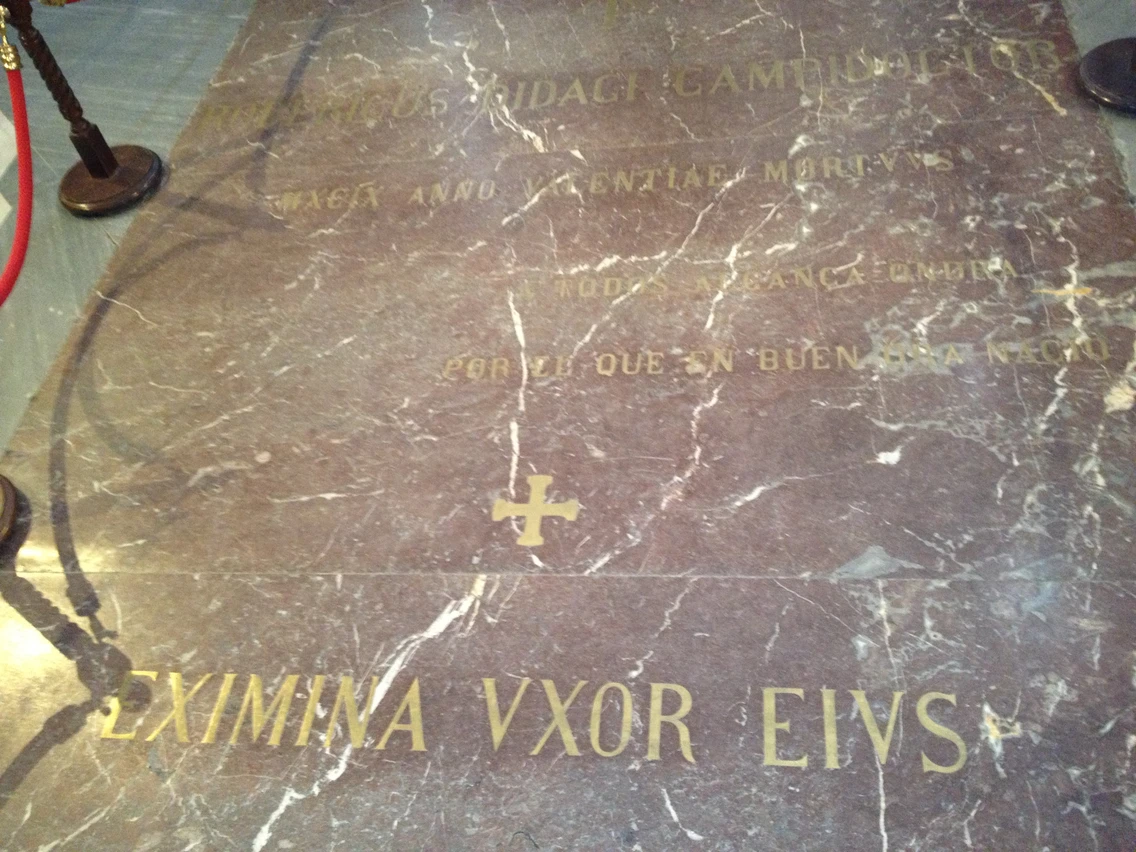

By the choir, there are exquisitely-carved chairs and intricate mouldings of Biblical and evangelical scenes. In front of the chorus is the burial place of Spanish hero, Rodrigo Diaz de Vivar, better known as El Cid, and his wife Doña Jimena Diaz, daughter of a certain Count Diego Fernandez de Oviedo.

El Cid was a Castilian nobleman and leader in medieval Spain. Brought up at the court of King Ferdinand the Great and later serving at the household of the king’s son, Sancho, he rose to become commander and royal standard bearer of Castile upon Sancho’s ascension to the throne. He led the military campaigns against Sancho’s brothers who were the rulers of Leon and Galicia that time, as well as against the Muslim kingdoms. He was exiled when Sancho was murdered and replaced by his ousted brother, Alfonso.

El Cid then fought for the Muslim rulers of Zaragoza, whom he protected from the domination of Aragon and Barcelona. Alfonso reconciled with him when he got defeated by the Almoravids from North Africa. El Cid worked for him but at the same time also worked as mercenary-general for other rulers, both Christian and Muslim. Late in life, he captured Valencia in the south, ruling it until his death in 1099. He was highly-regarded by both Christians and Muslims, earning the monikers El Campeador (The Outstanding Warrior) from the former, and El Cid (The Lord), from the latter.

In an age of hostility between the two religions, he demonstrated that it is possible to cross barriers and work with people whose culture is entirely different, and worse, stereotyped, by people from our own. This was indeed a noble feat. After his death, he became the legendary national hero of Castile, and the protagonist of Cantar de Mio Cid, a medieval Spanish epic poem.

I was surprised by how simple and unassuming the tomb was. It was just a single rose-coloured marble slab on the floor, cordoned off from the onlookers. We were told that the original tombs of El Cid and his wife, more ornate ones with effigies on top, are located at the Monastery of San Pedro de Cardeña. French soldiers stole their bones during the Napoleonic invasion of Spain and took them home to France. In 1927 they were returned to Spain and the remains were transferred to the cathedral’s transept. There is a Latin inscription on the tomb which translates to, “Brave and unconquered, famous in triumphs of war, lies in this tomb, Roderick the Great of Vivar.”

I paid my respects to the great hero then followed the audio guide toward the cathedral’s northern door where lies the golden staircase, Escalera Dorada, built in the 16th century and designed in the Renaissance style with Italian influences. In front of it, an elaborately-decorated carriage used to carry religious images at processions was parked.

According to the audio guide, this magnificent staircase has no practical use today as the Puerta de la Coroneira on the north side where it leads to is closed off, but it did serve as an inspiration for the design of the Paris Opera’s staircase.

A commotion at the back of the church caught my attention. Everyone suddenly rushed over there. I wasn’t sure what was happening but I decided to join the crowd. It turned out that it was time for the Papamoscas (Flycatcher) to do its hourly performance.

The Papamoscas is a robotic figurine located at the top of the nave. Its half-body, dressed in courtly style, looks over the façade of a clock. Every hour, it comes out carrying a score card on one hand, and with this same hand, rings the bell to signify the time. Its scary-looking face, almost devilish, appears even more ghastly as it opens and closes its mouth, also according to the hour of the day. Thus, the best time to view him is at noon where he repeats his act twelve times.

I heard from a tour guide nearby, providing a commentary to his small group, that the Papamoscas was named after the flycatcher bird which keeps its beak open hoping that it might catch a hovering fly at some point. This contraption dates from the 18th century, which replaces the earlier 16th century version. While it was indeed very entertaining, it had seemed odd to see something like this inside a Gothic church. I guess, medieval people do have their eccentricities, just like we do!

Photo Credits:

planetware.com, travelguide.michelin.com, catedraldeburgos.es, Zarateman (Wikipedia), agenciasic.es, Jose Luis Filpo Cabana (Wikipedia), RAntonio (Wikipedia), Cironte2008 (Wikipedia), equestrianstatue.org